Firefighting Ops & Weather – The Important Water Cycle

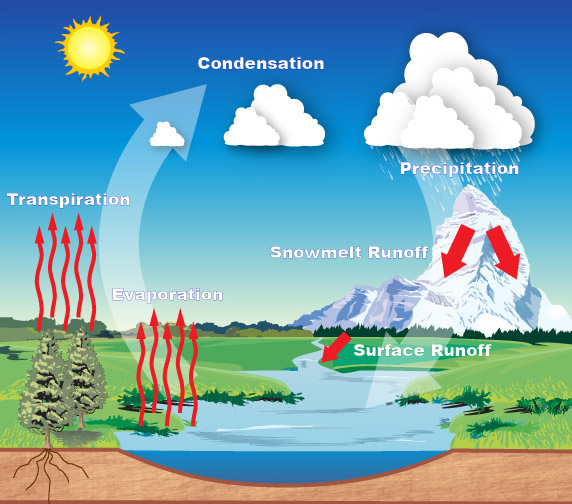

Our weather is critically dependent on the hydrologic cycle, or in simpler terms, the cycle of water.

Water has three primary forms (phases) that we experience here on earth. Two of the three are fairly easy to quantify – liquid water and ice. These states are both very tangible—that is, we can see them. Water vapor is much tougher.

We can certainly feel the difference between very moist and very dry conditions, but most of us are not able to accurately “feel” water vapor content. Like so many aspects of weather, the phase of water is continually in flux. As lake or ocean water evaporates, it is converted to vapor. As air is lifted, the vapor condenses into clouds. With sufficient condensation, rain may form to fill the water bodies once again.

From: https://www.srh.noaa.gov/jetstream/atmos/hydro.htm

Before continuing, let us establish some terminology for what we call certain transitions in water phase. It is important to note that water does not always need transition from gas to liquid to ice. Water can transition from any of the three phases to any other phase.

Condensation: Vapor to liquid

Deposition: Vapor to ice

Evaporation: Liquid to vapor

Sublimation: Ice to vapor

Freezing: Liquid to ice

Melting: Ice to liquid

A few more notes on the hydrologic cycle should be noted.

In the diagram, you’ll notice the term transpiration. A normal process of plant life is that water vapor is “transpired” as a part of its life processes. Why would this be important?

At certain times of the year, transpiration can significantly increase near-surface water vapor content (thus humidity and dew point.) Quite often, when August rolls around, it is sometimes interesting to watch the dew point over the corn belt region of the United States. As the corn reaches maturity, it transpires great amounts of water vapor.

To illustrate just how much, consider that the dew point temperature near the Gulf Coast is usually in the mid to upper 70s. During a hot August in Iowa, dew point temperatures may soar to the middle 80s along with temperatures in the middle 90s. This creates oppressive heat indices and thus very uncomfortable conditions. Plus, with such high dew point temperatures, the nighttime lows are often quite warm as well as, if you recall, the temperature does not drop to below the dew point temperature.

Most people think of 32F or 0C as the temperature which water freezes (or melts.) While keeping water in an ice state above 32F is not naturally occurring, liquid water temperatures below freezing definitely occur! Water freezes at 32F or thereabout only if there are impurities in the water. However, in thunderstorms, it is very common to have “super-cooled” water with temperatures around -4F or -20C. In fact, pure water in a lab environment can be cooled to -40 degrees before crystalizing into ice. Note that -40F and -40C are in fact the same temperature.

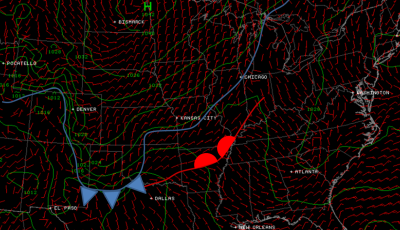

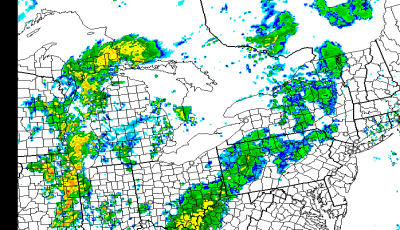

Next week we will take a look at air masses and fronts and how these can influence the weather while we operate at the fire scene. Knowing weather and how it to understand it will go a long way to saving our own when operating on any incident.