Identifying A Weather Front For Firefighters: Part 1

Frontal boundaries bring some of the most drastic changes in the weather that we perceive. Most of you who live in the middle latitudes (30-60 degrees north or south, North America) can probably recall a time where it was warm one minute and then the wind shifted and it started getting colder.

As a firefighter, one is very interested in sharp wind shifts for obvious reasons thus the importance of being able to identify a front.

I am going to make use of a resource that’s freely available on the internet that can be used to look at a multitude of meteorological parameters and includes both observational AND model data.

It is available at https://simuawips.com. Some of these data are not easily accessible anywhere else on the web. Yes there are maps out there that analyze fronts for you but they are updated at most every 3 hours and are analyzed at the synoptic scale meaning that errors of 60-120 miles are commonplace.

That’s unacceptable when examining weather for fire operations. When fighting a fire, do you want high levels of uncertainty as to when a front may arrive?

Of course not!

This is why it pays to be able to understand the very latest data yourself.

The Front Boundary

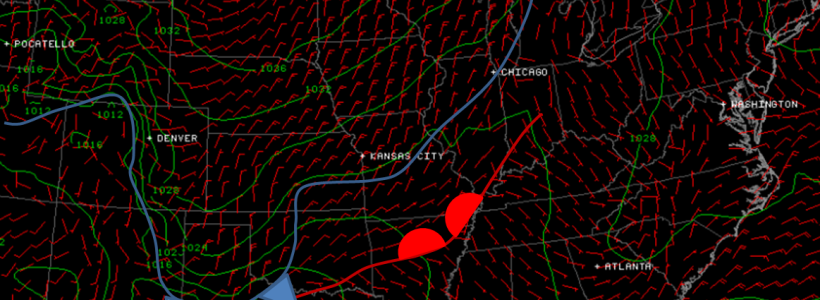

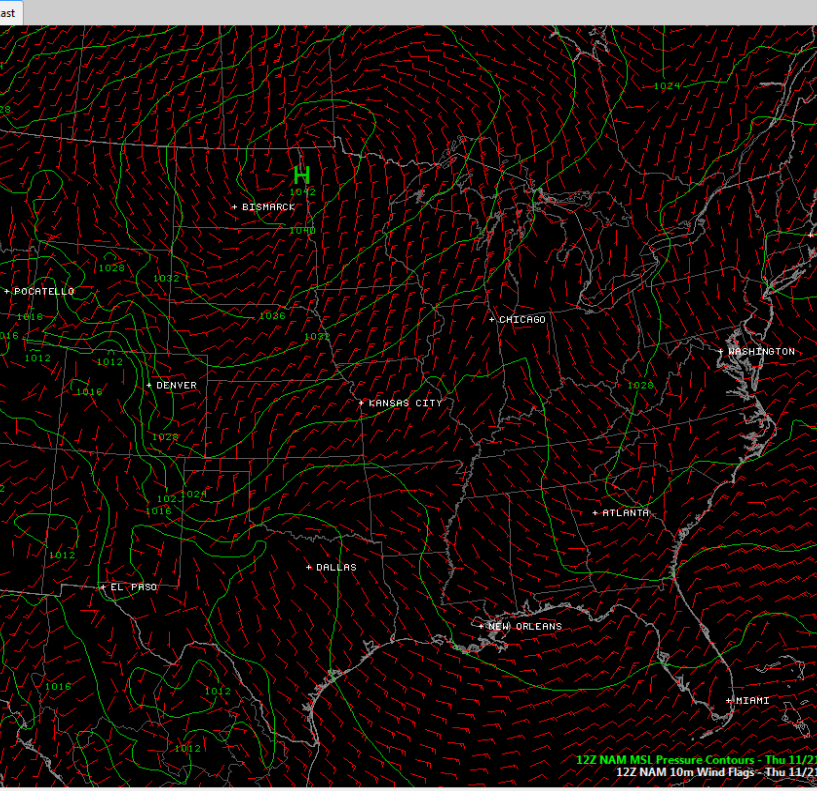

A much-anticipated frontal boundary was forecast to move into Texas late Thursday, Nov 21st and here is the forecast from Tuesday Nov. 19th. The contours in the map show lines of equal surface pressure and the wind barbs show wind direction and speed.

At first, the map may look confusing and meaningless. But, let’s dissect things and you’ll see it’s not hard at all to comprehend.

There is a high pressure center over the Dakotas near Bismarck (think mountain) and there exists a valley that extends from the Big Bend of Texas to Arkansas to Indianapolis to the top of Lower Michigan. On the other side of this valley is another ridgeline which runs up the Appalachian Mountains to near Boston.

In meteorology we call these valleys TROUGHS and the ridges…well…RIDGES.There also can be high pressure centers (HIGHS), such as near Bismarck and Low Pressure centers (or LOWS) of which this chart does not have an example. Just imagine a low like a Florida sinkhole.

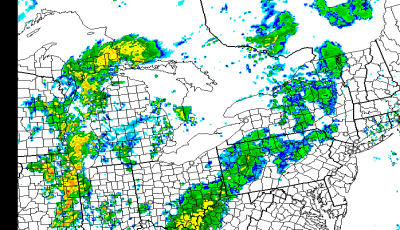

Next time we will continue the study on identifying frontal boundaries with a look at wind speed and direction, a very important item to know when working the incident scene.

Part 1 of 2