Temperature and Moisture Effects on the Firefighter

Temperature

In our introductory article we discussed weather as a whole but to understand how it affects us and our firefighting operations we need to break it into parts. So let’s shift gears a bit into how we measure weather.

In the simplest terms, weather is literally all about air and water and the characteristics derived from them. Fortunately, we are quite familiar with temperature, a measure of the amount of “heat” we feel. It is important to note, however, that when we feel cold, it is merely that the heat energy is less.

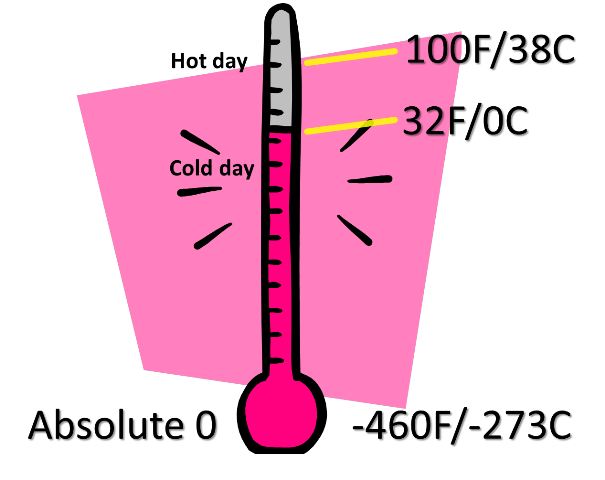

Remember back from high school when you probably learned about various temperature scales?

Remember absolute zero?

That is the complete absence of heat, as cold as it can get.

If you can envision the scale of temperatures in the graphic, it becomes apparent that, in the grand scheme of things, the variation in daily temperatures (as far as us humans go) is fairly small. Most of the world’s population usually experiences temperatures between about 0F to 100F with some larger excursions. However, even that variance is small as compared to the amount of temperature change to get to absolute zero. So, even when we get a cold front through our area, it is still heat energy which is driving the weather.

Moisture

The concept of atmospheric moisture and its impact is a bit more elusive to comprehend. Most of us are familiar with humidity, which is a measure of how much water vapor is in the air we breathe compared to the maximum water vapor that the air could hold at a given temperature. Humidity plays a big part in firefighting as the lower the relative humidity the more vigorously that fuels may burn.

Without going into equations, let’s see how temperature and humidity interact.

At 70°F, the air can hold about twice as much water vapor than at 50°F. Likewise, with each 20 degree drop in temperature, the maximum possible water vapor content is roughly halved. When the relative humidity is 100%, the air is holding as much water vapor as it can. More than likely, however, the water vapor is condensing onto dust or other particles which reveals itself as fog.

0% humidity would indicate the complete absence of water vapor. However, that does not occur in nature; though I have seen (and felt) what 1.8% RH feels like. While it feels nice at first, it doesn’t take long for one’s lips and face to dry out.

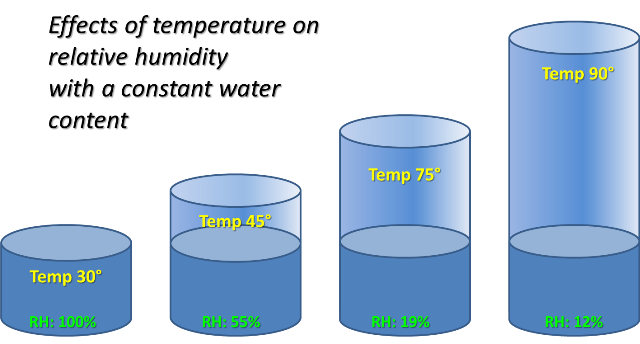

To better illustrate the concept of relative humidity (RH), let’s use the analogy of water in a set of glasses. In the example below, we take an air mass that is fully saturated (100% RH) when it’s 30 degrees outside. In practice, this could be a freezing fog situation.

Now, let’s increase the temperature through the day. As morning progresses and the temperature rises to 45 degrees, the RH is already down to 55%. By the time late afternoon rolls around, the temperature could be a warm 90 degrees F. Again, if no water vapor content changed, we’re now at 12%RH. That’s literally going from a very moist start to the day to one which would result in very favorable conditions for burning.

Next week we will discuss Relative Humidity and how it affects you and the incident.