Firefighting and Weather – The Cold Front

As firefighters operate in the outside environment it is crucial they be able to understand the current weather conditions in their region, what is predicted in their area and how to read and understand the messages and data provided to them by the National Weather Service.This is part of the art and science of firefighting. As you have learned, having knowledge in these special categories helps to ensure a safe and effective outcome of your incident.

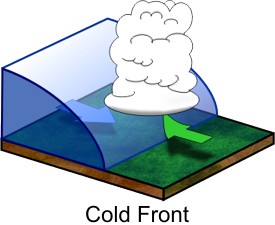

Today we are examining the cold front. These fronts can present signs of impending hazardous weather, a concern for fire operations.

Cold Fronts

Cold fronts are often the most noticeable frontal boundaries as they are often accompanied by storms and strong temperature changes. Along an advancing cold front, warm air (usually to the south in the northern hemisphere) is forced upward over the cooler intruding air mass. This characteristic is what often helps thunderstorms to form and potentially continue for hours or days.

Often, when storms fire along a cold front, storm processes may generate cold pools of air out ahead of an advancing storm system. These may create “gust fronts” extend for hundreds of miles along a line of storms. These gust fronts may or may not coincide with the larger scale cold front, but can certainly provide a focus for high winds and sharp changes in wind direction.

Fire Operations

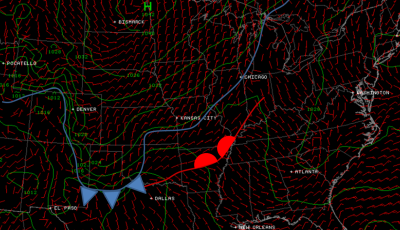

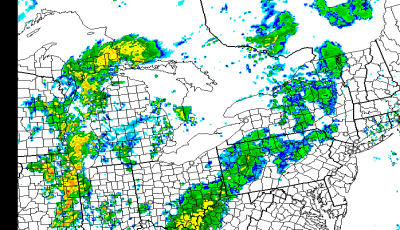

Cold fronts may also prove hazardous for ongoing fire operations. Strictly speaking the differences between an actual cold front or an initial gust front take some meteorological training to interpret, the important thing to note is that a front of any type will result in some characteristic change in your perceived air mass. The image below depicts a storm event along a cold front that is nearly coincident with the initial gust front.

Source: noaa.gov

Source: noaa.gov

Forecasting

Strong cold fronts are often fairly easy to predict when making a weather forecast as they are driven by significant weather features aloft. After all, most sensible weather that we experience on the surface are driven by things going on above our heads (pun intended.)

The weaker the system, the more difficult it is to conclude as to what precisely the surface weather will be. This is why you’ll see a better medium-range (1-5 days) forecast during the winter than one will often see during the summer when atmospheric forcing is quite weak.

If it’s going to be hot and dry, that’s one thing, but forecasting which day might see shower activity from local influences (seabreeze, lake breezes) during the summer is a whole different animal.

Next time we will move into the warm fronts, similar to the cold front these systems can play havoc with fire operations.